By Mohammad Sajjad,

In 1997 the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML), New Delhi through its Research Officer obtained the Maghfur Aijazi Papers. It suddenly reminded many that Aijazi (1900-1967) was one of the crusaders for India’s freedom, besides fighting for educational uplift of the Urdu speaking minorities in post-Independence period. The Times of India (15 August 1992, Patna) had written, “History has been unkind to him. A man who shared the travails for freedom with veterans like the Ali Brothers, Maulana Azad, C. Rajagopalachari, hardly shared the accolades that came in the way of his contemporaries after 1947”.

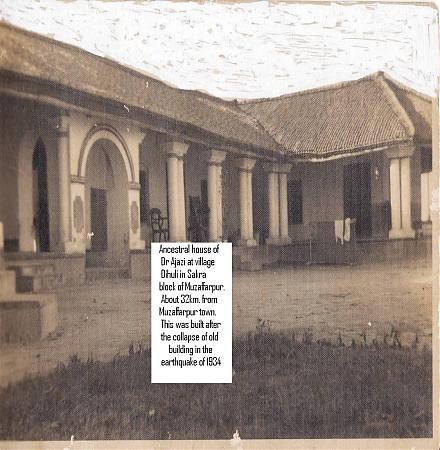

Born on 3 March 1900 at a village Dihuli in the Shakra thana of Muzaffarpur (Bihar), Aijazi was the son of a rich peasant Hafeezuddin, who had organized the peasantry against the European indigo planters. Aijazi received his elementary education under the supervision of Moulvi Mehdi Hasan, from the Madrasa Imdadiya, Darbhanga, and the Northbrook Zila School, Darbhanga. He had organized and mobilized the students for anti-colonial struggle, for which he was expelled out of the school; later on matriculated from the Pusa High School (Samastipur) and got admission in the BN College, Patna.

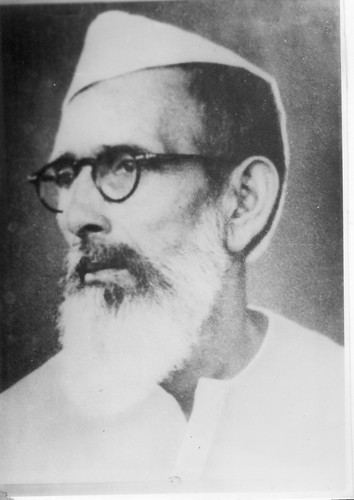

Maghfur Aijazi

Jumps into the Freedm Movement (1921):

In 1921 he jumped into the Non-Cooperation Movement, as he had to boycott the colonial educational institutions. He was joined by Prajapati Mishra and Khalil Das Chaturvedi. He got closer to the Ali Brothers, and along with Maulana Azad Subhani, Abdul Majid Daryabadi, etc., he became one of the founders of the Central Khilafat Committee. In 1921 he became a member of the Muzaffarpur District Congress Committee, and founded the Shakra Thana Congress Committee of Muzaffarpur, and was the Secretary of the thana unit of the Congress. The Nagpur session (December 1920) of the Congress had decided to set up District and lower units of the Congress.

As the anti-colonial struggle was becoming intense and spreading in the remote rural hinterlands, the colonial state became much vigilant and repressive. On 11 December 1921 police raided the office of the Shakra thana Congress, and a case was registered against Maghfur Aijazi; he was a delegate to the Ahmedabad Congress presided over by Hakeem Ajmal Khan. At this session Hasrat Mohani had moved the resolution of “Complete Independence”, seconded by Aijazi; the All India Khilafat Committee had also met there; Aijazi had met Abadi Bano Begum (Bi Amman), who had urged to raise a fund of Rs. 1,50,000 as “Angora Fund” for the Ottoman Khalifa to defend itself against the ongoing Imperialist onslaught.

Aijazi had become popular enough to have raised Rs 11000 to contribute to the “Angora Fund”. Sarojini Naidu had presided over the All India College Conference at Ahmedabad (1921), intending to raise a volunteer corps of students to join the anti-colonial struggle. Responding to it, Aijazi started the Congress Seva Dal with his “Aijazi Troupes” which recruited students to the cause of the freedom movement in north Bihar. He also met Mahatma Gandhi in the Sabarmati Ashram of Ahmedabad which electrified him, and he kept touring the villages of north Bihar during 1921-24 to mobilize the people; organized volunteer corps, formed Charkha Samitis, and Ramayan Mandalis; he launched a Seven Point Programme to raise fund for the Congress and Khilafat Committees of Muzaffarpur which contributed to help purchasing land for the District Congress at the Tilak Maidan of Muzaffarpur; selling khadi clothes, burning foreign clothes, boycotting other foreign goods, getting handful of grains (muthiya), women’s ornaments, and cash for the movement were some of the features of his mobilization schemes; in one such public meeting at his ancestral village, Dihuli, he burnt a bonfire of his own western clothes. Thus, besides Shafi Daudi (1875-1949), Aijazi was another leader to have popularized the anti-colonial mobilization in the rural hinterlands of north Bihar during the Non Cooperation Movement when he also launched campaign against liquor.

He had made a secret programme (to be implemented on 5th January 1922) of ‘subversive’ activities against the colonial state. The plot got leaked prematurely, and he was tried in case for that which was recorded as “Dihuli Conspiracy Case”. In the Gaya Congress (1922) Aijazi met C. R. Das, and he made fervent electoral campaigns for the Congress candidates in the municipal polls of 1923 despite the deaths of his wife as well as his father-in-law cum maternal uncle. He went on becoming much closer to Mohammad Ali Jauhar and Bi Amman; engaged himself in mobilizing people from Muzaffarpur to Banaras; attended the Kakinada Congress presided over by Mohammad Ali Jauhar. In a special session of the Congress (1923) presided over by Maulana Azad, he had demonstrated his regional patriotism by protesting against the issue of sitting arrangement whereby the delegates from Bihar were not given seat in the front row. His protest was admittedly on the issue of self-respect of the Biharis.

Aijazi went along with the Pro-Changer wing of the Congress, and had seconded the Kelkar’s proposal of right to self-determination for the people of the princely states. From there via Delhi he went Badayun and paid homage to a sufi, Aijaz Husain and added Aijazi to his name. On return he attended the Congress and Khilafat meetings at Motihari. In 1924 he contested the District Board elections 1924; the same year he was arrested by police as he had addressed a public meeting at Kishanganj (campaigning in the bye-elections for the candidature of Abdul Bari, 1882-1947) in violation of the government’s prohibition orders against entering into the district of Purnea.

On 28 July 1924, following Jauhar’s instruction he proceeded to Calcutta and took charge of the Khilafat Committee office, and there he came into contact with Subhash Chandra Bose who was engaged in mobilizing the students. During his stay in Calcutta, Aijazi constructed a masjid at Narkul Danga, surviving till date. At the Madras Congress session (1927), he met M A Ansari who had presided over the session; was in the forefront to boycott the Simon Commission (1928). He was the Secretary of the Khilafat Committee at that time. He expressed his dissatisfaction on the Nehru Report (1928), and along with Daudi he joined the Ahrar Party (1929) which was opposed to the communal separatist politics of the Muslim League. Aijazi was the Secretary and Daudi was the President of the Ahrar Party. In 1930 he mobilized people for the Salt Satyagrah, campaigned against liquor, and linked the social reform with the freedom movement; peeved at growing communal tension of the 1920s, he had also developed some inclination towards the Khaksar in 1931. In the calamity of the earthquake (15 January 1934), Aijazi undertook relief works.

Opposes League’s Two-Nation Theory, 1940-47

On 23 March 1940 the Muslim League at Lahore session passed a resolution demanding separate state for Muslims. Aijazi asserted his politics against this religious bi-national nationalism by launching his Jamhoor Muslim League, which merged with the Congress during the Quit India Movement. In 1941 he joined the Individual Civil Disobedience and mobilized the people of Shakra where the police had to resort to lathi charge, injuring Aijazi. His son had died on 25 July 1942, yet undaunted with this personal loss, he remained in the forefront of the Quit India Movement (August 1942); arrest warrant was issued against him, the police raided his house; he however continued his struggle underground; was arrested and put behind bars. On being released he undertook a campaign, “Cultural Conference” purported to educate the rural people about the growing menace of Fascism in Europe.

His popular movement against ‘Pakistan’ was met by sarcastic slogans by the people of Muslim League whose teenage cadres used to come to his house in groups shouting, “Aijazi! Ghaddaar-e-Qaum”, and spitting on the door of his house. He erected a team of few people in the town of Muzaffarpur to launch a door-to-door campaign persuading Muslims not to fall prey to the League politics.

Takes Up the Cause of Urdu

The Marginalization of Urdu by the votaries of the Nagri movement aided by the colonial state was increasingly becoming a settled fact in Bihar after 1862, and where Urdu had almost lost the battle in 1880. Yet, in the 20th century some attempts were made to keep the language and its script alive. In 1918, Zamiruddin (1862-1921) and Mahmud Shere had started the Bihar branch of the Anjuman Taraqqi Urdu (founded in 1903) in the Hugh Library; Patna; later Qazi Abdul Wadud (1896-1984) shifted it to Bankipur, and made it popular and dynamic movement. In October 1936, Abdul Haq had presided over the Urdu Conference in Patna’s Anjuman-e-Islamiya Hall, attended notably by Shafi Daudi, and Maghfur Aijazi, who became Vice President of the Bihar branch of the Anjuman Taraqqi Urdu, among many others.

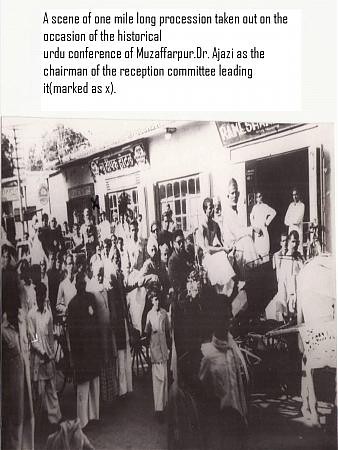

In 1929, the protagonists of Urdu had secured a concession that on experimental basis Urdu script will be allowed to be used by the government in the Commissioner’s Division of Patna. From 27 May 1937, the conferences (jalsa) for Urdu were organized first in Patna, followed by more than one thousand such mobilizational campaigns in rural Bihar. In June 1937, Mr. Md. Yunus (1884-1952), the first Premier (chief minister, April-July 1937) of Bihar had allowed the use of the Urdu script in government offices. His ministry also brought out a bi-lingual (Urdu/ Hindi) magazine called Mel Milap, and passed a Bill in the Assembly for protection (tahaffuz) of Urdu. On 28 August 1938, a Pact was signed between Rajendra Prasad (the then President of the Nagri Pracharini Sabha) and Abdul Haq (Baba-e-Urdu) in the Wheeler Senate Hall of the Patna University, where Gandhi’s proposal of “Hindustani” with both Urdu and Nagri scripts were agreed to be used in order to dilute the growing Urdu-Hindi divide. In 1940, Daaera-e-Adab (literary circle) was formed in the Patna University for promotion of Urdu literature. In 1941, again a mass rally was convened in Patna to re-assert the “Rajendra-Haq Pact”, which was followed by a massively attended ‘Tirhut Urdu Conference’ of Muzaffarpur on 6 to 8 July 1945, organized mainly by Betaab Siddiqui, and Aijazi. Encouraged with such a massive response, Abdul Haq, even went on demanding a Urdu University in 1946.

His engagement with the cause of Urdu went on to serve bigger purposes in the post-independence era. Soon after independence he urged upon the Congress government to ensure the following for the battered Muslims of post-partition era:

(i) The under-representation of the Muslims, more particularly in the police and military should be looked into, (ii) Urdu should be taken as a language of the local population and it should be accorded relevant privileges, (iii) Every district should have a Teachers’ Training College, (iv) Moulvis should be appointed to inspect Urdu maktabs (it was there during the colonial era), (v) Special officer to look into the issue of Muslim education should be appointed, (vi) there should be Urdu primary schools for boys as well as for girls, (vii) Every high School and College should have teachers for Urdu literature, (viii) Urdu translations of the school text-books should be made available, (ix) In the middle class school examinations Persian should be an optional language, (x) Urdu translations of the question papers for all school examinations should be made available, (xi) all government offices and judicial courts should preserve their records in Urdu language as well, and should send their replies to Urdu letters/applications in Urdu, (xii) The sign-boards/name plates of the government offices, roads, railways etc. should be in Urdu besides in Nagri and English.

In order to popularize the abovementioned demands, he distributed the pamphlet on a large scale in rural and urban areas, and carried out mass campaign, in which he regretted the fact that there is no provision of free compulsory primary education, and demanded that there should be conducted a special census to open Urdu schools in the relevant villages of Bihar. This campaign was sustained through an organization for the Bihar Muslims’ Educational, Economic and Social Uplift. This organization asserted that wherever there were 40 students with Urdu as mother tongue, necessary provision of Urdu teaching should be made by the government. Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s he sustained this movement for Urdu. To press such demands, on 4 July 1961, at Patna, he also met the Union government’s Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities. For the purpose he also appealed the people to keep writing to the respective District Education Officers (DEOs), and the District Superintendents of Education (DSEs), and he urged that a copy of those applications should be sent to him for the records of the organization he was running for the purpose. It is said that due mainly to his efforts, not less than 15 Urdu schools, (including the Makhdumiya Urdu Middle School of Saraiyaganj in the Muzaffarpur city) were established by the Bihar government in different villages of Muslim concentration in the then district of Muzaffarpur which also included Vaishali, Sitamarhi and Sheohar.

For these purposes he also organized mass rallies for the cause, first on 3-4 December 1960 in Muzaffarpur, and then on 4-5 June 1966 in Siwan (Saran), where he also made an announcement that the issue of Urdu will be an election issue in the forthcoming Assembly elections (1967). S. M. Aiyub (1910-64) had already made it an election issue in the 1962 elections by threatening to contest elections against the then Chief Minister, Binodanand Jha (1900-1971) of the Congress government (1961-63).

Aijazi worked hard and succeeded in getting started BA (Hons) and MA courses in Urdu literature in various colleges of the Bihar University, and he was the convener of the movement to have transferred the Patna headquarters of the Bihar University to Muzaffarpur; seeking parity with Hindi, he succeeded in having a nominated member in the Senate of the university on the Urdu quota.

In short, he engaged himself in the politics of linking Urdu with government employment.

Fights for AMU’s Minority Character, 1965

In 1965, he led a movement in the district for the minority character of the AMU, and launched mass demonstrations against the then Union Minister of Education, M C Chagla, in May 1965; and Aijazi urged upon the people to observe 16 July 1965 as the ‘Aligarh [Muslim University] Day’.

Congress alienates him after Independence

In November 1961 he had left the Congress and had joined the Swatantra Party, contested the 1962 Lok Sabha elections from Muzaffarpur as a formidable nominee of the Party. It is said that given the generally growing anti-Congress mood (rise of the Socialists) in the district of Muzaffarpur [in Dec’ 1957, from the Sitamarhi Lok Sabha, Acharya J B Kripalani had won; the Congress nominee had come 4th; and subsequently in a bye-election for assembly, a PSP candidate had won in Muzaffarpur defeating the Congress nominee; Asoka Mehta (1911-84), had defeated the Congress from Muzaffarpur Lok Sabha bye election in December 1957], Indira Gandhi had to make special campaigns for the Congress in Muzaffarpur, with speeches to polarize the votes along communal lines; consequently, Aijazi lost it even though he did secure as many as 58 thousand votes.

Aijazi had a multifaceted personality. Besides being an Urdu poet of some standing, he was Chairman, Muzaffarpur municipality (1952-58), and also led the trade unions of the Electric Supply employees, the Motipur Sugar Mill, the Arthur Butler’s Rail Wagon Workshop, the rickshaw pullers’ union; had founded the north Bihar Railway employees union, of which he was president, 1948-51; was also the secretary of the Muzaffarpur Sports’ Association, besides serving the Jamiat-ul-Ulema’s Muzaffarpur branch.

[His brother Manzur Aijazi (d. 1969) entered into the freedom movement in 1913; on the call of Mahatma Gandhi left his services in the Pusa Sugarcane Research Institute in 1919. Altogether he served 13 years of imprisonment. He was elected MLA from the Patepur Assembly constituency in 1957].

Thus, Aijazi’s contribution in the freedom movement, and in the post-independence era, in the strong grass-root campaign for linking Urdu with government employment, and his engagement also with trade unionism going much beyond merely ‘minority specific’, are few significant contributions towards strengthening India’s pluralist democracy.

[This is an abridged version of my Urdu essay published in Tahzib-ul-Akhlaq, February, 2004; more details in my forthcoming monograph, Contesting Colonialism and Separatism: Muslims of Muzaffarpur, Bihar since 1857.]

--

Mohammad Sajjad is Asstt. Prof. at Centre of Advanced Study (CAS) in History, Aligarh Muslim University.